Design and Deployment of TinyURL

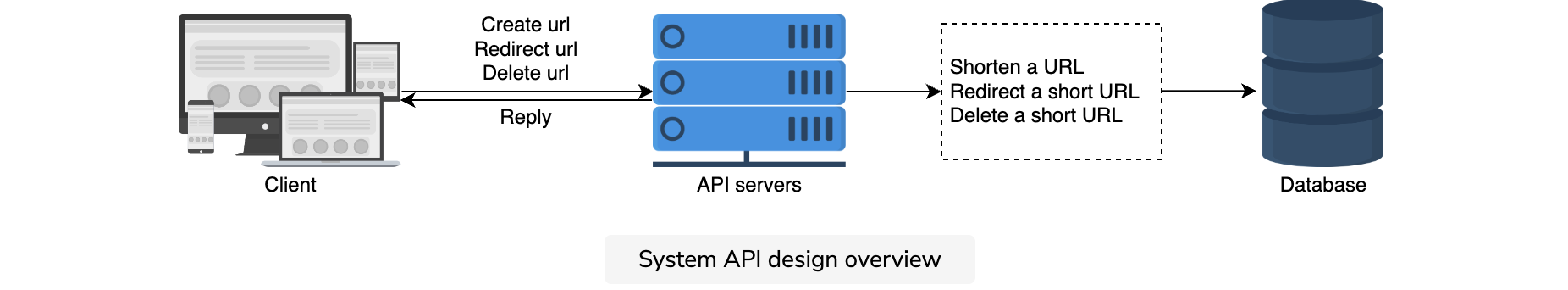

System APIs

To expose the functionality of our service, we can use REST APIs for the following features:

- Shortening a URL

- Redirecting a short URL

- Deleting a short URL

Shortening a URL

We can create new short URLs with the following definition:

shortURL(api_dev_key, original_url, custom_alias=None, expiry_date=None)

The API call above has the following parameters:

#

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

api_dev_key |

A registered user account’s unique identifier. This is useful in tracking a user’s activity and allows the system to control the associated services accordingly. |

original_url |

The original long URL that is needed to be shortened. |

custom_alias |

The optional key that the user defines as a customer short URL. |

expiry_date |

The optional expiration date for the shortened URL. |

A successful insertion returns the user the shortened URL. Otherwise, the system returns an appropriate error code to the user.

Redirecting a short URL

To redirect a short URL, the REST API’s definition will be:

redirectURL(api_dev_key, url_key)

With the following parameters:

#

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

api_dev_key |

The registered user account’s unique identifier. |

url_key |

The shortened URL against which we need to fetch the long URL from the database. |

A successful redirection lands the user to the original URL associated with the url_key.

Deleting a short URL

Similarly, to delete a short URL, the REST API’s definition will be:

deleteURL(api_dev_key, url_key)

and the associated parameters will be:

#

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

api_dev_key |

The registered user account’s unique identifier. |

url_key |

The shortened URL against which we need to fetch the long URL from the database. |

A successful deletion returns a system message, URL Removed, conveying the successful URL removal from the system.

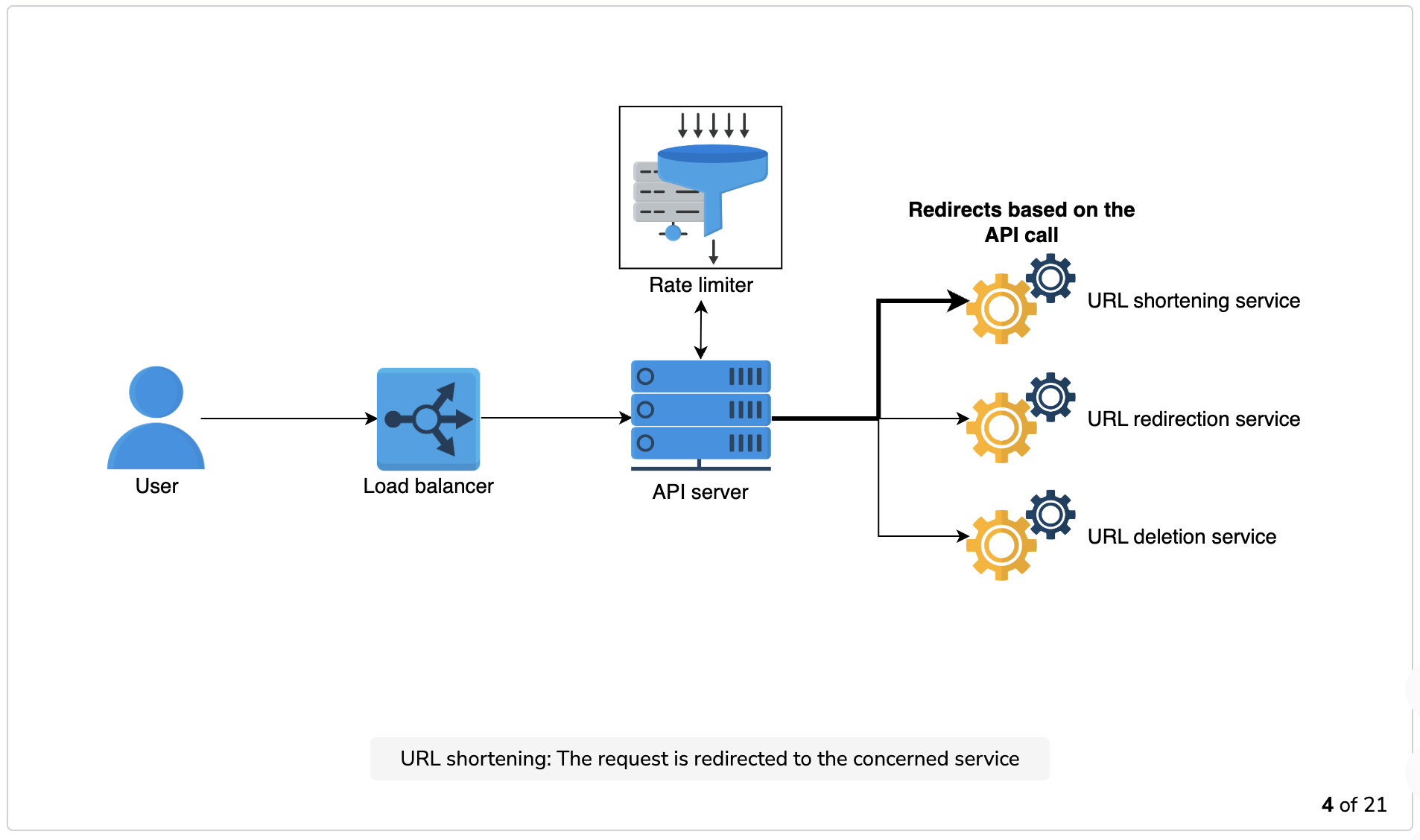

Design

Let’s discuss the main design components required for our URL shortening service. Our design depends on each part’s functionality and progressively combines them to achieve different workflows mentioned in the functional requirements.

Components

We’ll explain the inner mechanism of different components within our system, as well as their usage as a part of the whole system below. We’ll also highlight the design choices made for each component to achieve the overall functionality.

Database: For services like URL shortening, there isn’t a lot of data to store. However, the storage has to be horizontally scalable. The type of data we need to store includes:

- User details.

- Mappings of the URLs, that is, the long URLs that are mapped onto short URLs.

Our service doesn’t require user registration for the generation of a short URL, so we can skip adding certain data to our database. Additionally, the stored records will have no relationships among themselves other than linking the URL-creating user’s details, so we don’t need structured storage for record-keeping. Considering the reasons above and the fact that our system will be read-heavy, NoSQL is a suitable choice for storing data. In particular, MongoDB is a good choice for the following reasons:

- It uses leader-follower protocol, making it possible to use replicas for heavy reading.

- MongoDB ensures atomicity in concurrent write operations and avoids collisions by returning duplicate-key errors for record-duplication issues.

Question

Why are NoSQL databases like Cassandra or Riak not good choices instead of MongoDB?

Since our service is more read-intensive and less write-intensive, MongoDB suits our use case the best for the following reasons:

- NoSQL databases like Cassandra, Riak, and DynamoDB need read-repair during the reading stage and hence provide slower reads to write performance.

- They are leader-less NoSQL databases that provide weaker atomicity upon concurrent writes. Being a single leader database, MongoDB provides a higher read throughput as we can either read from the leader replica or follower replicas. The write operations have to pass through the leader replica. It ensures our system’s availability for reading-intensive tasks even in cases where the leader dies.

Since Cassandra inherently ensures availability more than MongoDB, choosing MongoDB over Cassandra might make our system look less available. However, the time taken by the leader election algorithm is negligible compared to the time elapsed between short URL generation and its first usage, so it doesn’t hamper our system’s availability.

----------------------

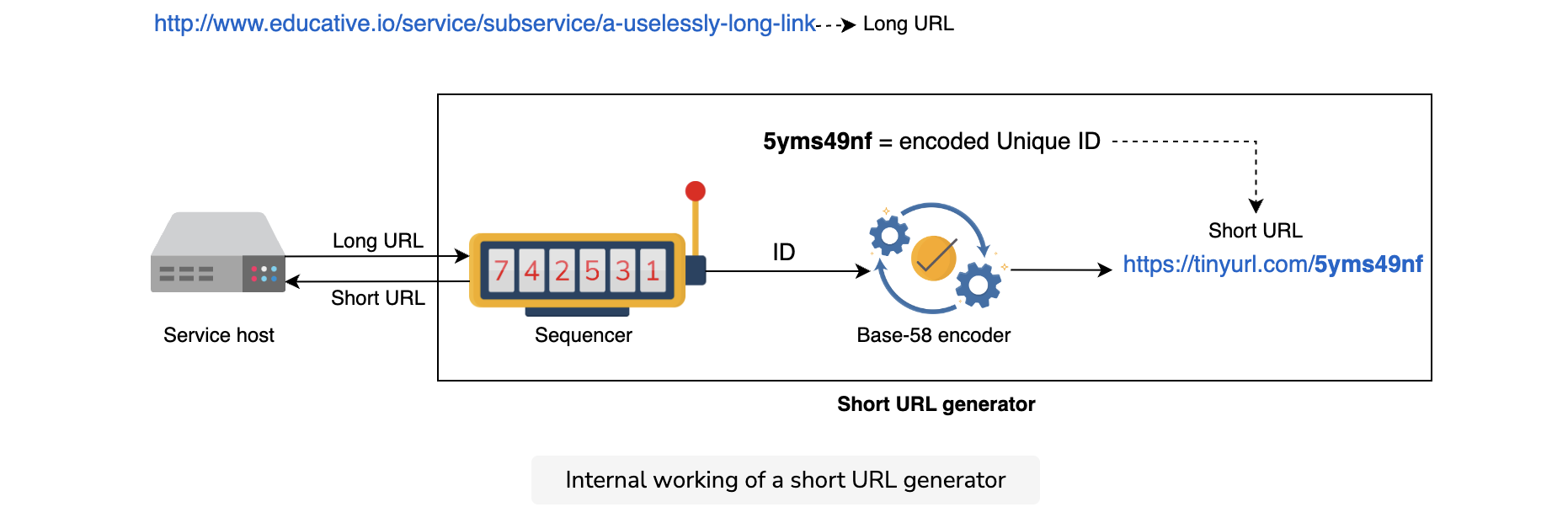

Short URL generator: Our short URL generator will comprise a building block and an additional component:

- A sequencer to generate unique IDs

- A Base-58 encoder to enhance the readability of the short URL

We built a sequencer in our building blocks section to generate 64-bit unique numeric IDs. However, our proposed design requires 64-bit alphanumeric short URLs in base-58. To convert the numeric (base-10) IDs to alphanumeric (base-58), we’ll need a base-10 for the base-58 encoder. We’ll explore the rationale behind these decisions alongside the internal working of the base-58 encoder in the next lesson.

Take a look at the diagram below to understand how the overall short URL generation unit will work.

Other building blocks: Beside the elements mentioned above, we’ll also incorporate other building blocks like load balancers, cache, and rate limiters.

- Load balancing: We can employ Global Server Load Balancing (GSLB) apart from local load balancing to improve availability. Since we have plenty of time between a short URL being generated and subsequently accessed, we can safely assume that our DB is geographically consistent and that distributing requests globally won’t cause any issues.

- Cache: For our specific read-intensive design problem, Memcached is the best choice for a cache solution. We require a simple, horizontally scalable cache system with minimal data structure requirements. Moreover, we’ll have a data-center-specific caching layer to handle native requests. Having a global caching layer will result in higher latency.

- Rate limiter: Limiting each user’s quota is preferable for adding a security layer to our system. We can achieve this by uniquely identifying users through their unique

api_dev_keyand applying one of the discussed rate-limiting algorithms (see Rate Limiter from Building Blocks). Keeping in view the simplicity of our system and the requirements, the fixed window counter algorithm would serve the purpose, as we can assign a set number of shortening and redirection operations perapi_dev_keyfor a specific timeframe.

Question 1

How will we maintain a unique mapping if redirection requests can go to different data centers that are geographically apart? Does our design assume that our DB is consistent geographically?

We initially assumed that our data center was globally consistent. Let’s look at the problem differently and consider the opposite case: we need to filter the redirection requests based on data centers.

Solution: An simple way of achieving this functionality is to introduce a unique character in the short URL. This special character will act as an indicator for the exact data center.

Example: Let’s assume that the short URL that needs redirection is service.com/x/short123/, where x indicates the data center containing this record.

In this solution, if the short URL goes to the wrong data center, it can be redirected to the correct one. However, if a specific data center is not reachable for a specific short URL (and that URL is not yet cached), the redirection will fail.

Question 2

How will the data-center-specific caching handle an unseen redirection request?

Since we’ve assumed the data-center-specific caching solution for our system, a case needs highlighting: handling unseen redirection requests by our system.

Scenario: The scenario entails receiving an unknown redirection request at a data center. Since the local cache wouldn’t have that entry, it would fetch that record from the globally consistent database and place this entry into the local cache for future use.

Question 3

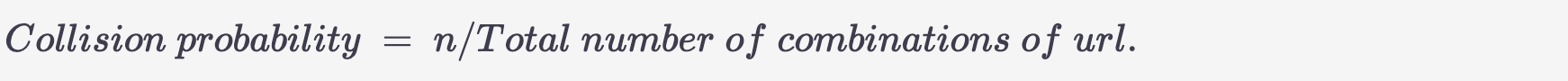

What is the probability of collision when we ask the short URL generator for a new short URL?

We ask the sequencer for a unique ID and by the definition of our sequencer’s design, there will never be duplication in IDs. We then encode those IDs, which also ensures no duplication. Hence, the regular short URL generation process ensures no duplication in records.

Now let’s consider the case of custom short URLs. Since the user is providing the short URL, there can be a duplication. We can easily calculate the probability of this collision by taking into account the size of the database containing short URL records.

Let’s assume there are n already generated short URLs in the database. The probability that the user-provided custom short URL will be similar to an already existing one can be given by:

With growing n, the collision probability would increase, ranging from 0 when n=0 and 1 when n=total number of combinations.

This calculation assumes that the user selects a custom short URL randomly and equally likely from the set of allowed combinations. In reality, few words are more popular than others. So our probability can be seen as a lower bound on the probability of collusion.

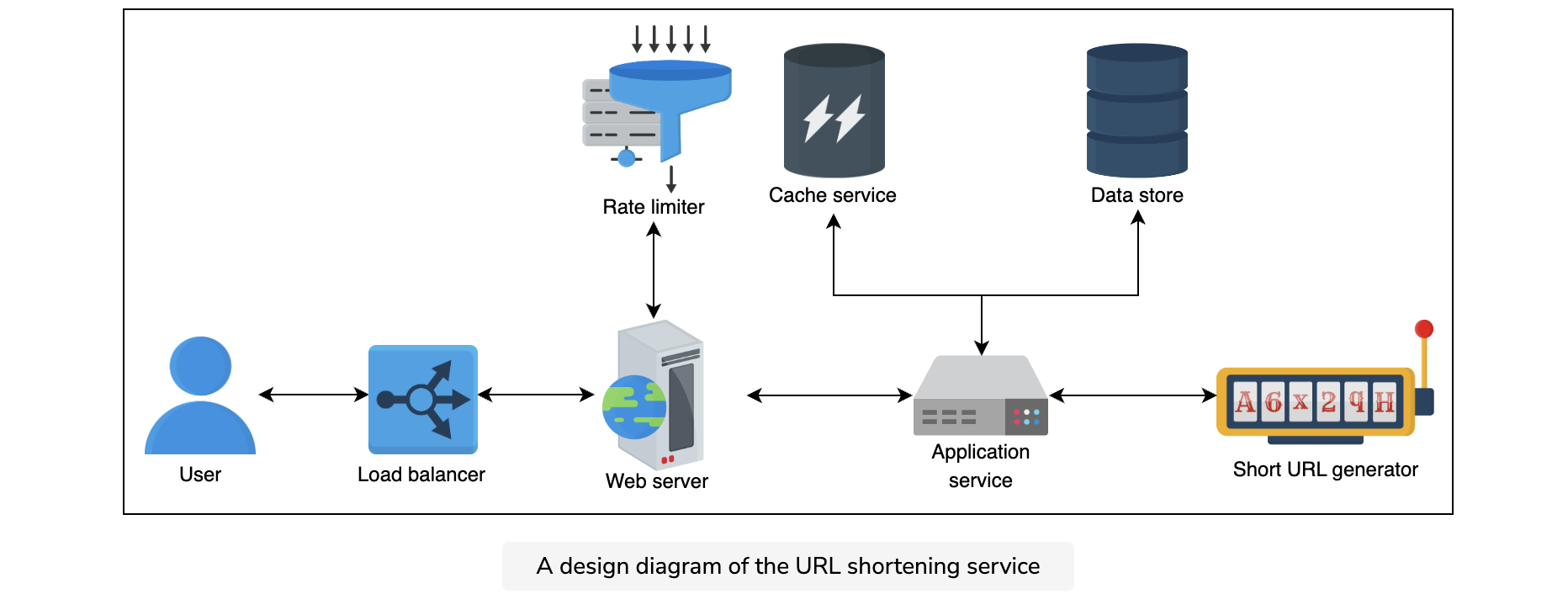

Design diagram

A simple design diagram of the URL shortening system is given below.

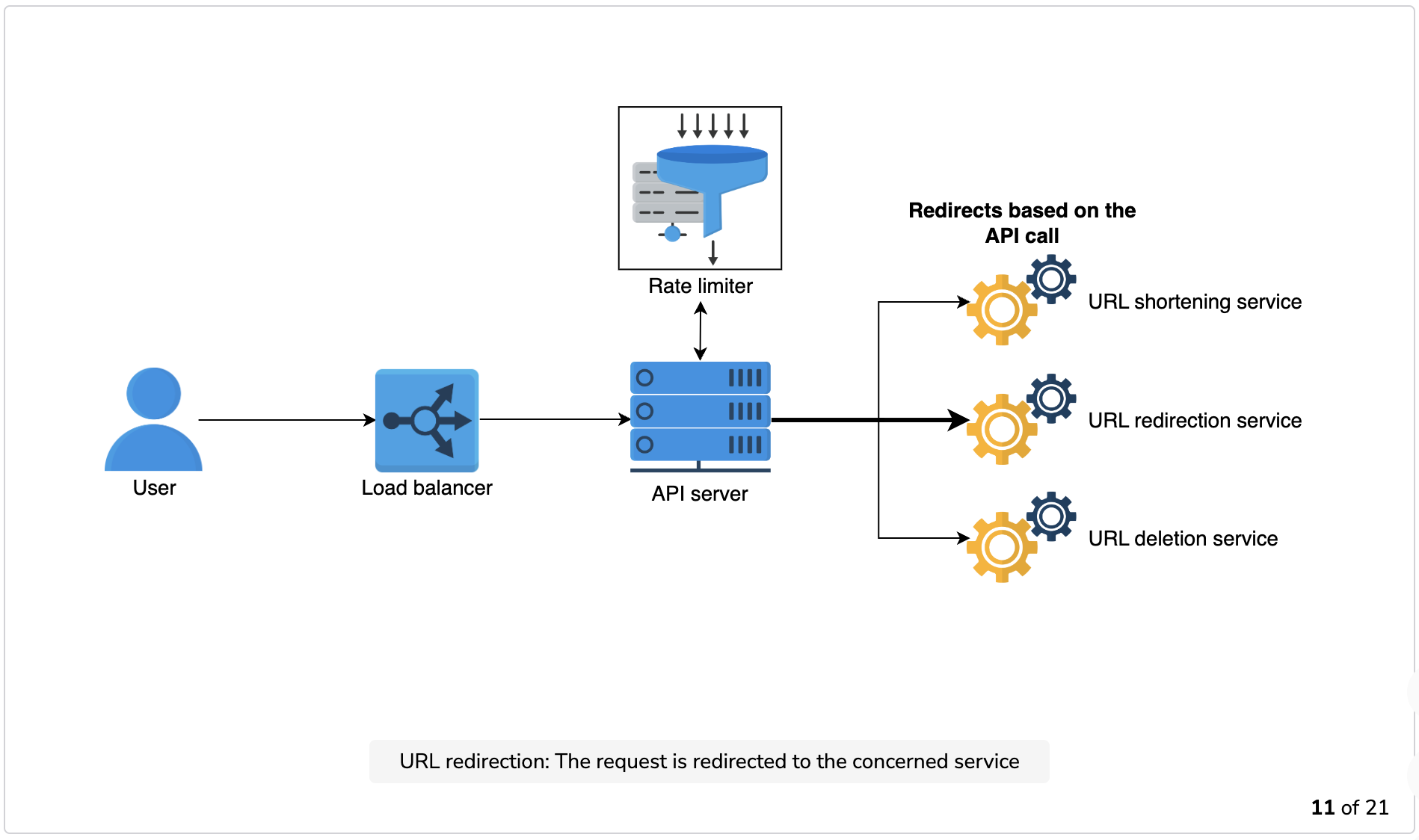

Workflow

Let’s analyze the system in-depth and how the individual pieces fit together to provide the overall functionality.

Keeping in view the functional requirements, the workflow of the abstract design above would be as follows.

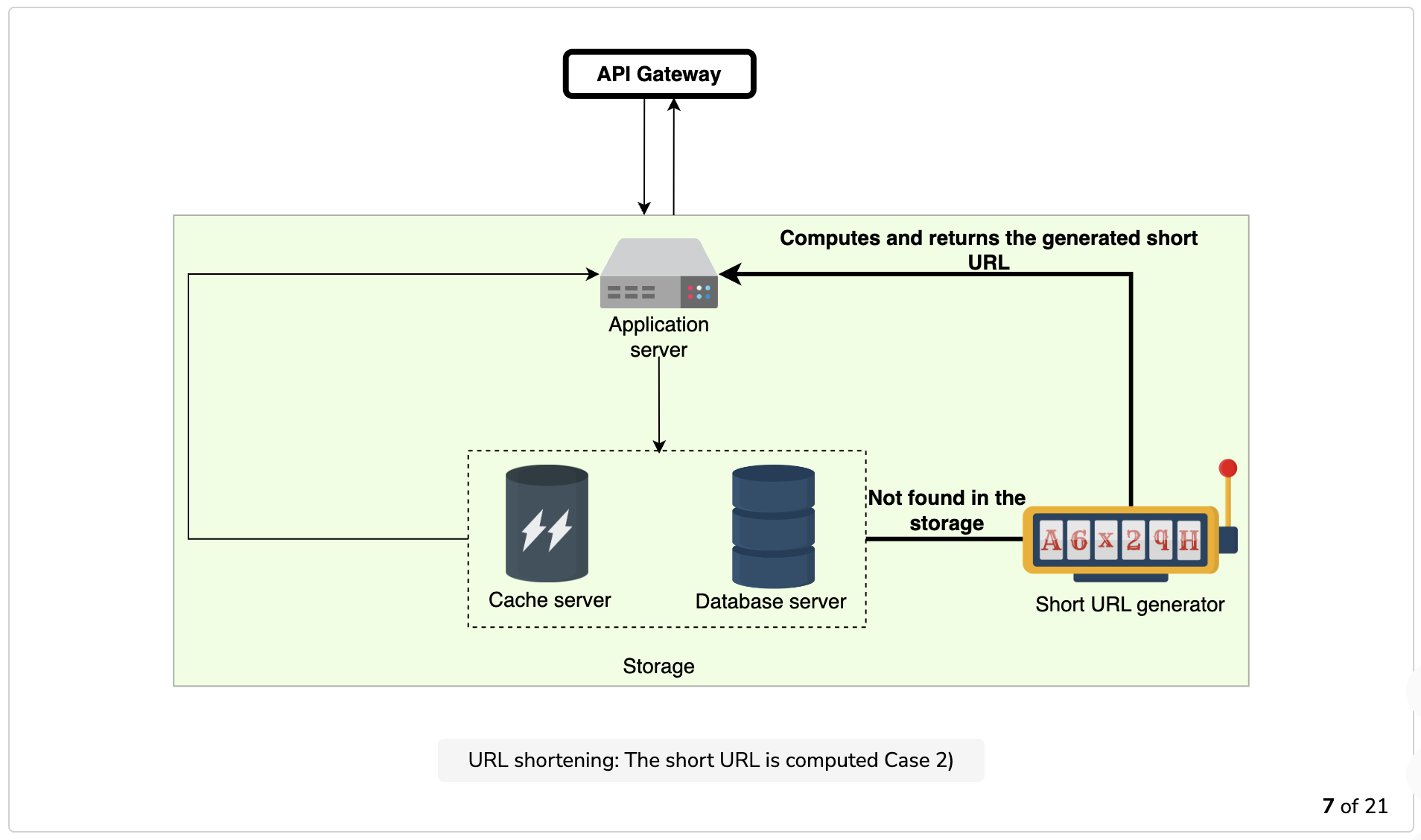

- Shortening: Each new request for short link computation gets forwarded to the short URL generator (SUG) by the application server. Upon successful generation of the short link, the system sends one copy back to the user and stores the record in the database for future use.

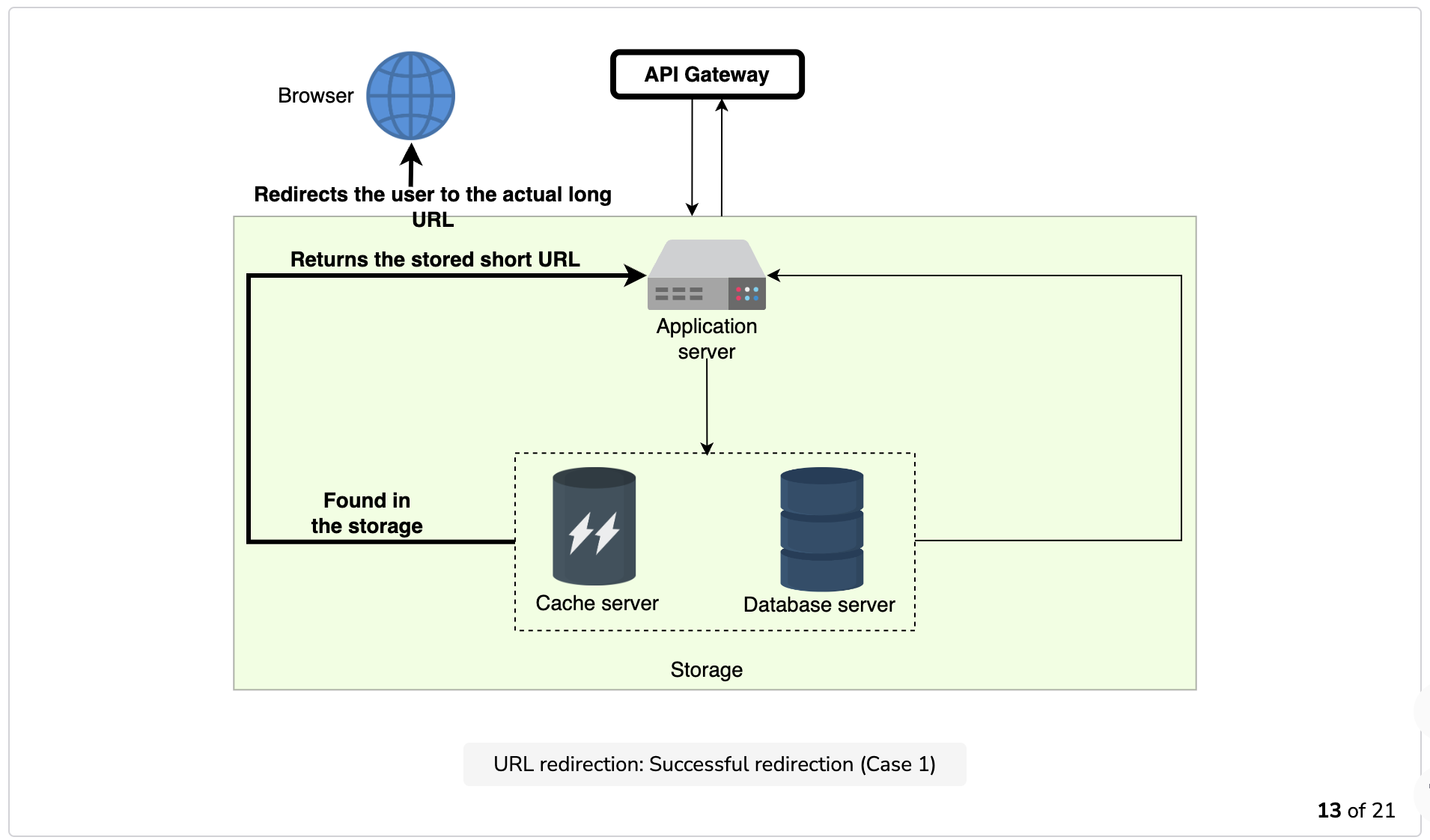

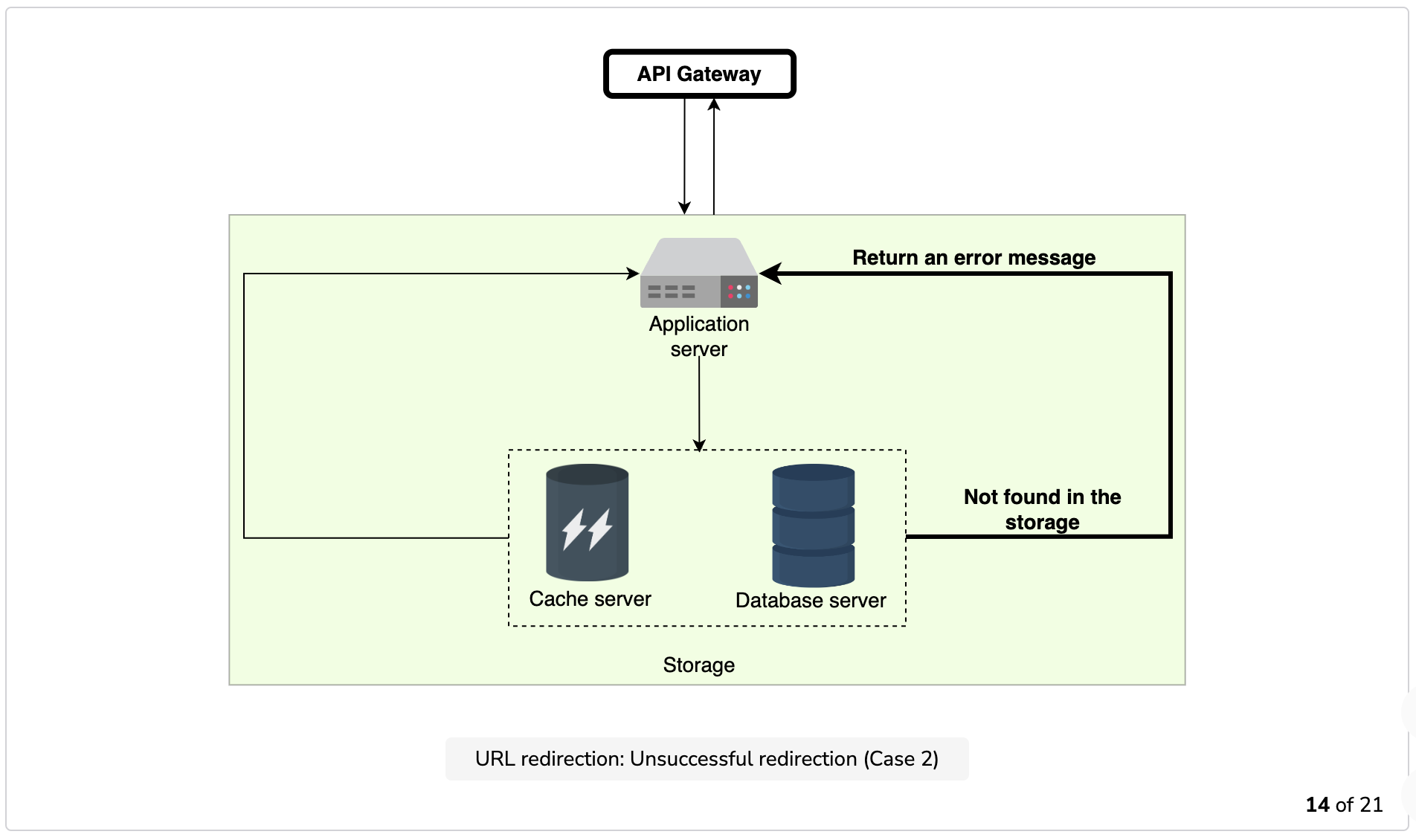

- Redirection: Application servers, upon receiving the redirection requests, check the storage units (caching system and database) for the required record. If found, the application server redirects the user to the associated long URL.

- Deletion: A logged-in user can delete a record by requesting the application server which forwards the user details and the associated URL’s information to the database server for deletion. A system-initiated deletion can also be triggered upon an expiry time, as we’ll see ahead.

- Custom short links: This task begins with checking the eligibility of the requested short URL. The maximum length allowed is 11 alphanumeric digits. We can find the details on the allowed format and the specific digits in the next lesson. Once verified, the system checks its availability in the database. If the requested URL is available, the user receives a successful short URL generation message, or an error message in the opposite case.

Question 1

How does our system avoid duplicate short URL generation?

- Computing a short URL for an already existing long URL is redundant, and the system sends the long URL to the database server to check its existence in the system. The system will check the respective entry in the cache first and then query the database.

- If the short URL for the corresponding long URL is already present, the database returns the saved short URL to the application server which reroutes the requested short URL to the user.

- If the requested short URL is unavailable in the system, the application server requests the SUG to compute the short URL for the requested long URL. Once computed, the SUG sends back a copy of the requested short URL to the application server and another copy to the database server.

Question 2

How do we ensure that two concurrent requests for a short URL do not overwrite?

Concurrency in handling URL shortening requests is essential, and we achieve it as follows:

- MongoDB ensures consistency by locking and concurrency control protocols, preventing the users from modifying the same data simultaneously.

- In MongoDB, all the write requests go through the single leader and hence exclude the possibility of race conditions due to the serialization of requests via a single leader.

-------------------------

Question

How does our system ensure that our data store will not be a bottleneck?

We can ensure that our data store doesn’t become a bottleneck, using the following two approaches:

- We use a range-based sequencer in our design, which ensures basic level mapping between the servers and the short URLs. We can redirect the request to the respective database for a quick search.

- As discussed above, we can also have unique IDs for various data stores and integrate them into short URLs. We can subsequently redirect requests to the respective data store for efficient request handling.

Both of these approaches ensure smooth traffic handling and mitigate the risk of the data store becoming a bottleneck.

--------------

The illustration below depicts how URL shortening, redirection, and deletion work.

Question

Upon successful allocation of a custom short URL, how does the system modify its records?

Since the custom short URL is the base-58 encoding of an available base-10 unique ID, marking that unique ID as unavailable for future use is necessary for the system’s integrity.

On the backend, the system accesses the server with the base-10 equivalent unique ID of that specific base-58 short URL. It marks the ID as unavailable in the range, eliminating any chance of reallocating the same ID to any other request.

This technique also helps availability. The node generating short URLs will no longer need to maintain a list of used and unused unique IDs in memory. Instead, a database is maintained for each of the lists. For good performance, this database can be NoSQL.

The above part explains the post-processing of a custom short URL association. Some further details include the following:

- Once we generate IDs, we put them in the unused list. As soon as we use an ID from the unused list, we put it in the used list. This eliminates the possibility of duplicate association.

- As encoding guarantees unique mapping between base-10 and base-58, no two long URLs will have the same short URL.